Silvicu M A G A Z I N E ture

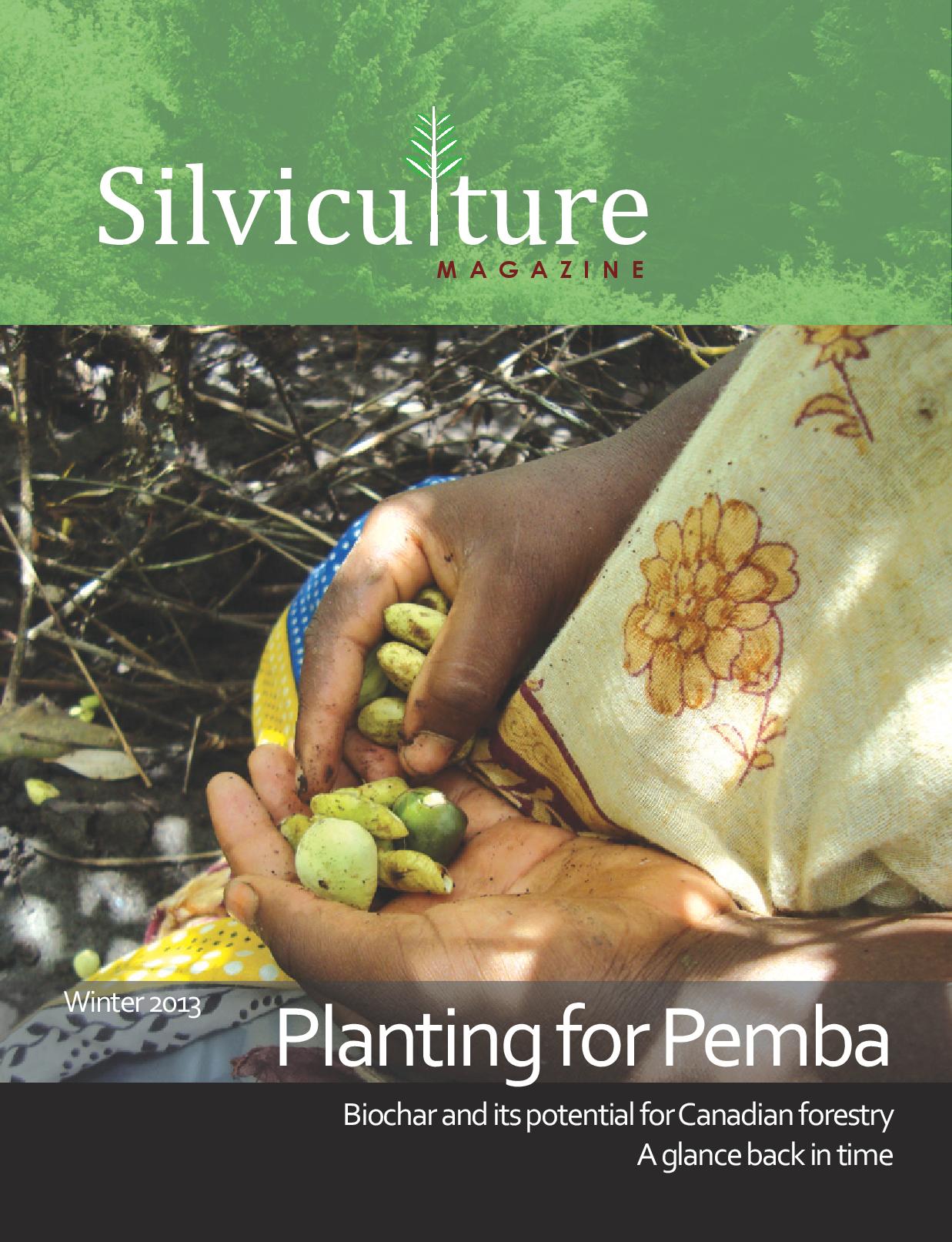

Planting for Pemba Winter 2013

Biochar and its potential for Canadian forestry

A glance back in time

Want to get a competitive edge and

reach thousands of readers in a target market?

Promote your products or services to our expansive community of:

• Industry Associations

• Silviculture Contractors

• Foresters

• Government Practitioners

Contact us at [email protected] or 778.882.9156

www.silviculturemagazine.com

Advertise in Silviculture Magazine!

Experience growth and success with Canada’s

exclusive publication for the Silviculture industry.

• Reforestation workers

• Woodlot Owners

• Researchers

• Students

Silvicu M A G A Z I N E ture

Cover photo: Woman sorting seeds for planting

in a community nursery, 2009 Pemba Tanzania

Photo courtesy of CFI (Canadian Forests International).

Publisher Kate Menzies

Designer Krysta Furioso

Editor Dirk Brinkman

Associate Editor Erin Kendall

Silviculture Magazine

601 East Pender St., Vancouver, BC. V6A 1V6

Phone 778 882 9156 | Fax 604-628-0304

Email [email protected]

www.silviculturemagazine.com

4 Biochar and its potential in

Canadian forestry

12 A glance back in time:

Poor decision making

21 The ultimate tree planting shovel

7 Focus on Safety

8 Readers’ Lens

9 Notes From the Field

16 WSCA Report

17 Ontario Report

18 International Forestry

Students’ Association

19 B.C. First Nations Forestry Council

22 Forest Health

features

columns

contents

4 Silviculture

Biochar and its potential in

Canadian forestry

By Sean Thomas

Throughout the boreal forest region and indeed much of Canada,

fire is the primary natural “disturbance agent” — the means by which

older forest stands are naturally replaced by younger stands. The

situation immediately after a fire can appear quite unpromising:

charred remains of canopy trees and loss of understory vegetation,

including regenerating trees. However, an observation familiar to

many foresters is that post-fire stands “green up” remarkably quickly.

A few years after a moderate-intensity fire, understory vegetation

is generally thick and future canopy trees are growing vigorously.

A number of processes contribute to post-fire regeneration and

rejuvenation. Many tree species show adaptations to survive fire

events (e.g., thick insulating bark, high belowground storage), or to

regenerate by seed following fire (e.g., the serotinous cones of Jack

Pine). In addition, nutrients previously stored in living parts of trees

have been released into the system, and soil temperature is increased

by a reduction in litter. However, something much less obvious also

contributes to post-fire forest rejuvenation: namely, a phenomenon

that has been termed the “charcoal effect”. In experiments in the

1990s in Scandinavia, additions of charcoal to soils were shown

to increase nitrogen uptake and growth of some trees, and result in

a proliferation of understory vegetation. Some fern species would

only establish where charcoal was present. An initial hypothesis

of the main mechanism responsible was the capacity of charcoal

to absorb growth-inhibiting phenolic compounds associated with

the leaf litter of certain understory species, in particular Ericaceous

shrubs (blueberries and their kin). Early research also showed

that charcoal strongly impacts a variety of soil processes, resulting

in increased litter decomposition rates, increased soil pH, and

increased availability of nitrogen and cations such as calcium and

magnesium.

In the last few years research interest on charcoal in soils has veritably

exploded. A major motivation stems from the long persistence of

charcoal in soils. Wood chips added to soil decompose within a few

years, and the half-life of larger logs is often only 20-25 years. In

contrast, 90%+ of charcoal remains present for at least 100 years,

and a large portion is likely to be present for 1000 years or more.

This longevity is of great interest in terms of carbon “sequestration”.

Charcoal is >95% carbon, and diversion of organic waste material

from agriculture and forestry into charcoal on a large scale could

in theory be an important mechanism to remove carbon from the

atmosphere and store it in a form that will remain put for a long

period of time. Unlike other proposed types of carbon “capture”,

addition of charcoal to soils has considerable potential to have

additional beneficial effects that have nothing to do with climate

change. The term that has emerged for charcoal intended for use

as a soil amendment is “biochar” (Fig. 1), with the “bio” referring

to its biological source. Biochar as a climate mitigation strategy

has recently been promoted by the likes of Al Gore, James Hansen,

and James Lovelock.

Biochar basics

Complete combustion of wood, as occurs under high oxygen

conditions, produces wood ash as an end product. Wood ash is

generally very alkaline (pH 9-13), and depleted in lighter elements

such as nitrogen. Although there are cases in which wood ash

has been used for agricultural liming, it is generally not beneficial

as a soil amendment to enhance tree growth. Pyrolysis is the

thermal decomposition of biomass under low oxygen conditions;

it is a chemical reaction that one would recognize as a kind of

smoldering fire. Although simple to initiate, pyrolysis is a complex

chemical process. The main chemical products of wood pyrolysis

include syngas (composed of hydrogen gas, carbon monoxide, and

a variety of gaseous carbon compounds, especially ethylene and

methane), pyrolysis oils (heavier organic molecules that are liquid

at room temperature), and charcoal. Wood vinegar, consisting of

recondensed water and water-soluble organic compounds including

acetic acid and acetone, may also be produced. Pyrolysis has been

around a long time as an industrial process: some types of “town

gas” produced during the gaslight era were essentially pyrolysisgenerated

syngases.

The chemical and physical properties of biochar vary greatly

depending on pyrolysis conditions, such as peak temperature, and

also on the properties of the organic matter used as feedstock.

Biochar can be produced at temperatures of anywhere from 250-

900°C. Biochar produced at low temperatures (say <400°C) tends

to retain more carbon, and have a lower pH and porosity; higher

temperature biochars (say >550°C) retain less carbon and have

higher pH and porosity. Some types of feedstock present problems

for producing biochar useful as a soil amendment. Some animal

wastes (such as chicken manure), as well as urban compost sources

have quite high levels of salts (sodium chloride and others) that

remain present in charred material. Construction waste material

is typically mixed with metals and plastics, and can be expected to

produce chars that have unacceptable levels of toxic contaminants.

Contamination concerns are resulting in rapid efforts to develop

consistent labeling and quality assurance for trade purposes.

Biochar certification is likely to follow.

The properties of biochars that may result in a beneficial “charcoal

effect” remain a topic of considerable research interest. A number

5

matched to specific soil types and forest

communities.

What benefits are to be expected in terms

of increases in forest growth and yield?

At present nearly all published data are

from agricultural systems. A meta-analysis

(quantitatively compiling results from

numerous studies) published in 2011

found that on average biochar additions

resulted in a ~10% increase in crop yields

in agricultural trials (almost all conducted

in the tropics). However, if one considers

only trials in which soils were acidic and/

or coarse-textured, the gains in yield were

~20-30%. Also, there are other cases in

which larger growth enhancements have

been documented; moreover, growth

enhancement effects can continue for

many years after biochar has been added

to a soil.

Research trials on tree growth responses

in Canada have only been initiated in the

last year or so. Pot experiments examining

first year growth responses of a number of

Canadian tree species were completed in

my lab in October 2012 (Fig. 2). Results

are currently being analyzed for peerreviewed

publication, but it is clear that

results are not so clear cut: tree species

vary in responses, and both positive and

negative responses can occur. One

possible explanation for negative effects

is that early tree growth responses may

be strongly influenced by ethylene emitted

by biochars, but this remains speculative.

Understanding the mechanisms for effects

will clearly be critical to developing

biochars that maximize benefits and are

suited to specific tree species and soils.

Potential of biochar as a forest

product

There is considerable popular interest in

biochar as a soil amendment, and a range

of companies in the US and elsewhere are

marketing biochar for horticultural use. In

addition to its potential use for gardens

and houseplants, biochar has a number

of other important market niches. The

low weight of biochar makes it particularly

attractive for green roof and urban forestry

applications where minimizing soil mass is

important. The high capacity of biochar

to absorb a wide variety of chemicals also

has generated great interest in its use on

contaminated soils, including industrial

brownfields and on mine tailings. In an

agricultural context, biochar may be best

considered a substitute for lime: biochar

commonly has a liming potential much

greater than dolomitic limestone, and is

expected to continue to reduce soil acidity

over a much longer time. This specific

product substitution may also be important

in a forestry context: in Ontario the most

common forest soil amendment has been

lime added to acidified soils in sugar bush

operations. Biochar has an additional

potential advantage in that it can be

directly valued in terms of sequestered

carbon.

of mechanisms are now thought likely

to contribute to beneficial effects on

plant growth. Biochar generally bears a

negative charge, and serves as a cation

exchange site in soils. In addition, biochar

commonly has a remarkably high surface

area, and physically sorbs a great variety of

substances, including negatively charged

plant nutrient forms such as phosphate and

nitrate. The high surface area of biochar

also enhances soil water holding capacity,

and its low density will generally reduce soil

bulk density and so enhance soil aeration

and root penetration. Some properties

of biochar may, however, have negative

effects on plants. Freshly produced biochar

may absorb mineral nutrients to such an

extent that they are unavailable to plants,

suggesting a need to “prime” biochar by

adding nutrients. In addition, recent work

has shown that many biochars outgas

significant quantities of ethylene, a potent

plant hormone with unpredictable and

species-specific effects on plant growth

and development.

Potential for biochar use as a forest

soil amendment

In many respects it is “natural” to consider

biochar as a soil amendment in the

context of Canadian forestry. Charcoal

is something that naturally occurs in to a

greater or lesser extent in essentially all

forest ecosystems in Canada. One can

therefore anticipate that native plants

and other organisms, in particular soil

microbes and fauna, will be able to cope

with some level of biochar in the soil.

Adding charcoal to logged stands may

better “emulate” natural disturbance.

From current understanding of biochar

effects on soil properties, positive effects

on forest productivity would be expected in

many systems. Moreover, there is a high

potential to create “designer” biochars

Fig. 1. A handful of biochar.

Photo by Nathan Basiliko.

6 Silviculture

Wood fiber is generally regarded as a

superior feedstock for biochar production.

Other feedstocks, in particular animal

wastes and some agricultural residues,

commonly result in biochars with less

desirable characteristics in terms of element

content and properties like porosity. Wood

fiber is also likely to be more uniform and

predictable as a feedstock source. Of

course there are many other potential

uses for wood fiber in, for example, wood

composite products; however, most such

applications still result in residues that

could be used as a biochar feedstock.

Charcoal production is an ancient

technology, and there are a variety of

commercial units available geared toward

production of charcoal for barbequetype

markets. Simple “retort” systems,

mainly designed for on-farm processing

of agricultural waste, can also be

obtained. However, efficient conversion

of sawmill waste, in particular sawdust

and bark, to biochar, will demand highcapacity

purpose-engineered machinery.

Engineering emphasis to date has generally

been on pyrolysis products other than

biochar, in particular pyrolysis oils, which

have important potential as industrial

chemical feedstocks. Integrated systems

that efficiently produce a set of products

remain an important engineering goal.

Conclusions

Biochar is very likely to emerge as an

important new aspect of the forest industry

in Canada in the years to come. An

obvious driver initially will be market

opportunities for sawmills and other

wood processing facilities to turn waste

materials into new products that have an

added economic value in terms of carbon

credits. Use of biochar as a forest soil

amendment is most likely for high-value

stands subject to soil acidification, in

which biochar may be a cost-effective

and more permanent substitute for lime.

Urban forest applications may also be

important, as may intensively managed

high-input systems, such as hybrid poplar.

The economics of biochar will also depend

strongly on the development of carbon

markets and regulatory frameworks to

encourage climate change mitigation.

Sean Thomas is Senior Research Chair, Forests and

Environmental Change in the Faculty of Forestry, University

of Toronto. Dr. Thomas’s research focuses on tree functional

biology and forest carbon processes, with current funded projects

examining biochar impacts on tree growth and soil processes.

Email: [email protected]

Fig. 2. Trees vary in their response to biochar additions. Comparison of growth responses to biochar of (A) red maple (Acer rubrum)

and (B) yellow birch (Betula alleghaniensis) (C = control; B = biochar addition treatment, consisting of sugar maple sawdust pyrolized

at a peak temperature of 525°C added at a rate of 5 t/ha. Photo by Tara Sackett.

7

Focus on Safety

and supervisors to take a hard look

at themselves and determine by what

examples they are setting and leading by.

Observe the next time you go onto the job

site what people are doing (and not doing),

look for those “little things”. For instance

personal protective equipment is an easy

one; if someone is not wearing their hard

hats, eye/ear protection, are they likely to

follow the lockout procedure that takes

15 minutes, or that detailed maintenance

program? Probably not.

The true test in this exercise is not just

observing what people are doing, but

how you handle it. Before you hand out a

reprimand, ask yourself one final question,

“what have I done as this persons’ superior

to encourage this behaviour”?

If you can be honest with yourself, you

will find a golden opportunity within your

personal accountability to become a true

business leader.

Barbara McFarlane is the Executive Director for the New

Brunswick Forest Safety Association. She holds a degree in

Forest Engineering from the University of New Brunswick, a

Certificate in Adult Education from St Francis Xavier University

and is a Certified Health and Safety Consultant.

By Barbara MacFarlane

Safety in Business

A word….safety.

Did you cringe? Did your mind go to your

latest order by a workplace safety officer?

Did you feel your bank balance shrink?

Did you think about training records?

Did you think about the law and how

darn confusing it is to know what you’re

supposed to do? Did you think about an

accident, a near miss?

Another word…business.

Did you think of safety at all?

On October 4th in Miramichi, New

Brunswick the 3rd annual national meeting

of forest safety associations took place.

Representatives were present from British

Columbia, Saskatchewan, Ontario, Nova

Scotia, New Brunswick and Newfoundland.

At such meetings, current trends and

common issues are discussed and tools

and solutions are shared. The most

interesting thing I’ve noticed year after

year is that no matter how different our

provincial industries may seem, we are

not that different after all. One common

and reoccurring issue that arose again this

year is how to engage industry leadership

in health and safety.

To many, the term ‘safety’ (unfortunately)

represents a cost (like an accident or a

training course) or something that is apart

from their daily activities (like a safety talk).

However, the reality is that safety needs

to be fully integrated into one’s overall

business. It should just be how things

get done - safely. In fact, I believe that

segregating safety and using terms like

‘safety leadership’ and ‘safety culture’

have only stifled what so many of us health

and safety professionals are trying to do,

which is to fully integrate safety to the point

where it happens unconsciously.

How do we get there? The biggest step

for any business owner is to recognize that

safety is part of their business; whether they

address it or not, it’s there. As Reynold Hert

of BCForestSafe said at our October 2012

meeting, “every company has a safety

program, whether or not it’s making or

costing them money is the question”. So

if you are a business owner, ask yourself

“does my safety program make or cost

me money”? And if you answer “I’m not

sure” or “I don’t know” than I’ll bet it is

costing you.

Recognizing that safety is part of your

business is one thing, recognizing how

to initiate change in your business to

improve on it is something else. As a

business owner/manager/supervisor

you have the capacity to make things

happen. As Stephen Covey said “I am

personally convinced that one person can

be a change catalyst, a “transformer” in

any situation, any organization. Such an

individual is yeast that can leaven an entire

loaf. It requires vision, initiative, patience,

respect, persistence, courage, and faith to

be a transforming leader.”

A great leader is someone who champions

a message and rallies, follows not with

what they say but with their behaviour. A

great leader embodies a strong and clear

message such that their followers are

compelled to impress and emulate them

because they believe in them so deeply…

and not because of what they say but

because of what they do and what they

stand for. Remember the business mantra

that your lowest standard will become your

employees’ highest expectation.

In business and in safety it’s often said

that if people are not doing the little things

than they are not doing the big things.

So I challenge all owners, managers

8 Silviculture

DO YOU HAVE A

GREAT SHOT?

We’d love to include

your photo in an

upcoming issue of

Silviculture!

Email

[email protected]

Photo by Scooter Clark

Photo by Jeremy Cameron

Reader’s Lens

9

A Tree Planting

Misadventure

By Stephanie Page

Widow-maker: nickname used to describe

a falling snag. Snag: a dead or dying tree.

East of the Rockies there is a stretch of

Albertan forest familiar to tree-planters. After

a brutal day of planting white spruce and

pine in an overgrown, thorn riddled, wasp

infested, three-year-old fly block somewhere

between the swamps of Swan Hills and the

sweet canola fields of High Prairie, we were

waiting there impatiently for the helicopter

to come.

The skies began to fill with dark, purple

clouds. The wind was violent; we could

hear branches snapping in the treeline.

The thunder was chaotic; we could see

lightening in the distance. The rain began to

fall; we spotted the helicopter flying towards

us. The pilot couldn’t maneuver the wind to

make the designated landing site, so he put

the chopper down on the other side of the

cut-block. We didn’t have much time. Time

is always on a tree-planter’s mind. If we

didn’t make the chopper we’d have to wait

out the storm on the open block. Or worse,

if the sun went down before the storm let up

we’d have to stay in the forest overnight with

nothing but our rain gear, wet cigarettes and

empty lunch bags. We ran to make time.

We ran down the muddy trail, over fallen

logs, through wispy grass and into a shallow

ravine towards the chopper. I didn’t feel

scared. I don’t think anyone did. It was

tree-planting business as usual. Thunder.

Lightening. Rain. Hail. Snow. Wind. Bears.

Bugs. Thorns. Nettle. Waiting. Hurrying.

Hiking. Sweating. Shivering. Flying. Falling.

Jumping. Tripping. Bleeding. Mending.

Giving up and getting up to plant again the

next day.

I heard a thunderous crack that didn’t belong

to the sky and my supervisor hollered,

“TREE!!”. I looked up from the edge of the

ravine and saw the thick, sixty-foot widowmaker

falling perfectly towards us. Then I

felt scared.

I couldn’t go left. I couldn’t go right. I

couldn’t go forward. I only had time to throw

myself backwards and brace for impact. The

widow-maker slapped the ground and sent

woody debris flying into the air. The last thing

I saw was my friend dive into the mud and

disappear beneath the trunk...

The Dogon, a Malian ethnic group, have

an interesting relationship with trees. They

believe the forest is alive and in flux, while

villages are stagnate and fixed. Rocks move.

Trees move. Animals know human intention.

The forest is home to spirits and these spirits

can attack. It is a force that gives and takes.

Trees give life, but can also bring death.

They prefer to trim branches than to fell

whole trees. Wood is used thoughtfully and

hardly ever wasted. The Dogon believe the

forest replenishes itself, so they exert very little

control over it and plant very few trees. Their

conception of the forest is directly related to

how they treat it and is in direct opposition

to how I conceived of it before that sixty-foot

widow-maker knocked some sense into me.

(Milton, 1996)

I can assure you that when a tree falls on

you in the forest, it makes a sound. It seems

louder than thunder. It seems faster than

lightening. Its presence seems so abundant

that its escape from your attention seems

impossible. How then, could a gigantic

falling tree have remained invisible to me

until I had placed myself in its trajectory?

I opened my eyes. I was covered with leaves

and twigs. The largest branches had just

missed me, but my friend was still buried

beneath the tree.

“Where is he?!”, someone yelled. I didn’t

know. I began to panic. Then some branches

Notes from the Field

moved and he pulled himself out from under

the trunk.

He stood up, patted down his body and

yelled, “I think I’m okay!” Except for a busted

ankle, he was.

We pulled ourselves together and made the

chopper. The pilot maneuvered the storm

with finesse, fought the turbulence and

returned us to camp safely. I didn’t feel safe

though. I felt lucky.

The only reason I can write about that

widow-maker as a cautionary tale of treeplanting

misadventures is because time lined

up perfectly, so that a potential disaster

turned out to be a near miss instead. What

if I had jumped forward? What if the trunk

had lined up a few degrees differently to my

friends body? What if my supervisor hadn’t

yelled out? What if we had just paid more

attention?

It’s interesting to think about how a treeplanter’s

perception of the forest influences

their safety. Many of us, in our familiarity with

the cut-block and its hazards, may forgot

to respect the power of this environment. I

failed to assess my surroundings thoroughly

that day and found myself rushing towards

a falling snag. I was focused on making the

chopper and became inattentive. If you’ve

been planting for awhile you’re skin is

probably thick and the forest may even feel

like a second home. Scaring away bears,

working in a volatile environment and

braving a bush camp for months changes

a person’s understanding of discomfort and

danger. When the forest is your second

home and when you feel like you have

control over your work environment, it

becomes easy to undermine hazards on

the cut-block. This season I’ll be thinking

about the forest a little differently. I’ll be

thinking about how some people perceive

the forest as all powerful and relate to it more

cautiously. I’ll be keeping my eyes open for

snags and thinking about how lucky we were

to have escaped that widow-maker.

Milton, Kay 1996. Environmentalism and Cultural Theory:

Exploring the role of anthropology in environmental discourse.

London: Routedge. Pp. 106-141

Stephanie page has been planting trees for five years and

currently works for Next Generation Reforestation in Western

Canada. In the off-season she lives in Montreal and studies

at McGill University and can be reached at stephanie.page@

mail.mcgill.ca.

10 Silviculture

Those of us who have worked in silviculture know it as an industry

that cultivates a unique and incredibly valuable combination of skills.

Consider the conditions; unpredictable forces of nature, physical,

emotional and mental fatigue and stress, community dynamics, logistics,

remote locations and the repetitive nature of the work. Those who thrive

in this environment may move up to management positions or develop

their own contracting companies. Others pursue new endeavours,

but all have developed a gamut of skills and experience increasingly

recognized as having incredible value.

The next article is the first in a series that looks at amazing people of

our ilk who showcase the true value of skills and experience developed

over years in reforestation work. We explore and celebrate their

remarkable capabilities and the diverse ways in which their experience

in reforestation ultimately contributed to new and interesting directions

in their lives and work.

Planting for Pemba

Tree planters empowering change in rural Africa

By Zach Melanson | Photos courtesy of CFI

Very few people have ever spent a season planting trees in the clear-cut

swamps, rock cap, and mountains of our vast Canadian landscape. If

they did, they would likely find it somewhat horrifying. After four planting

seasons, I have become accustomed to working in remote areas,

among tangles of broken sticks and swarms of blackflies. I earned good

money and likely injured my body beyond repair, but the thing that

kept me coming back was the people. In tree planting camps it’s cliché

to indulge this sentiment, but for most planters, it rings true. A friend

and fellow tree planter, Laura Neals describes this experience well,

“A tree planting camp operates like a community. You live together.

You eat together. You work together. It’s easy to connect with each

other because you all share this common experience. There’s a sense

when you’re tree planting that you’re all in it together.” I would argue

that it is exactly this sense of community that links tree planters across

Canada to communities half way around the world.

The story of our organization; Community Forests International, begins

in the Spring of 2007, while swapping travel stories around a camp

fire and ruminating on the potential for change in the world. A friend

and fellow tree planter, Jeff Schnurr , shared his experience of a recent

trip to a small, isolated African island called Pemba. Jeff had been

living on the island for 6 months before returning to Canada to plant

trees. While in Pemba, he made friends with Mbarouk Mussa Omar,

a community leader who was working for a small NGO working

to preserve endangered coastal regions and provide education on

sustainable fishing practices. Being that Pemba is a remote Island with

few tourists, Jeff the “tree farmer” had piqued their interest. Mbarouk,

along with a group of local fishermen and farmers approached Jeff

to help start a tree planting initiative on tracts of degraded land. Jeff

was keen to help in any way he could, and began writing proposals

and visiting communities, communicating with locals the possibility of

growing trees for fruit, fodder and home construction.

When Jeff returned to Canada to plant trees, he shared his experience

on the island with myself, and others. A small group of us decided

to help, making a pact to dedicate two years of our lives to support

Pembans in their efforts.

Notes from the Field

Woman planting a mango tree near Tundaua, Pemba 2008

Mbarouk speaking to villagers on the islet of Kokota about the successes other

communities have had planting trees on the main Island of Pemba. 2012

11

Pembans had been subsistence farming and fishing since before

recorded history and pressure on their resources increased in step

with population growth. Today, trees could be planted to stabilize

coastlines, to improve soil quality, and provide cover on this intensely

hot tropical island. Furthermore, the islanders were importing many

staples from the mainland like mango, papaya, and wood poles for

home construction, which could be easily grown on the island. What

was missing was the initial investment in infrastructure and technical

assistance to get communities growing trees.

Our goal was simple enough, start small by helping a handful of

villages on the island of Pemba grow trees on community-owned land

for economic and environmental benefit. We accomplished this by

building low-cost nurseries in seven communities, and hiring Mbarouk

and a few local experts to visit villages and provide support.

In Canada, news of Pemba spread quickly through the camp, and

soon we had organized a fundraiser to help Pemban communities

build nurseries and grow their own seedlings. We picked a day where

planters could donate a portion of their earnings, in the form of trees,

to support the project. We called it “Plant for Pemba” The premise

being that for every tree planted in donation, several more would

spring up on the island. Laura Neals remembers one fundraising day

in particular, “It was my first year crew bossing and we had the most

miserable weather. It was a torrential downpour of near-freezing rain.

By four o’clock no one could feel their hands, but our day was far from

over. Most of the camp planted until eight-thirty that night. It was awful,

but no one complained. On that day, everyone got tough. It didn’t

matter how cold it was. It didn’t matter how late it was. Everyone felt

like they were a part of something special.” Laura donated over 4000

trees that day, the equivalent of about $380 dollars; all the money she

had earned. The camp followed her lead and we raised over $6000.

With the help of Brinkman & Associates Reforestation, Laura, and

hundreds of other planters, CFI has grown its presence on the island,

working alongside thousands of people in 14 communities. To date,

Pemban’s have planted 35 species of trees and over 700,000 seedlings

in total. Communities engaged in these initiatives collect seed from

local sources, pack the seedling containers, nurture, grow and then

plant the seedlings. What makes this project stand apart is its approach;

each community has full ownership and control of their nurseries and

the trees they plant. They decide what trees to grow and for what

purpose. CFI understands that Pemban’s are the experts, and no one

is better equipped to innovate long-term solutions than those within

the community. By Planting for Pemba, Pemban silvicultural experts

are employed and necessary funds are raised to get the projects off the

ground, helping create a collaborative partnership that works toward

positive social, economic and environmental change on the island.

Canadian tree planters and the people of Pemba have shown us that

collectively, we have the skills, resources and knowledge to care for

the environment and the people who live within it.

If you are a crew boss or supervisor who would like help organizing

a Plant for Pemba day, contact Zach Melanson at zach@

forestsinternational.org. Also please consider donating to Community

Forests International’s Pemban projects. For more information please

visit CFI at www.forestsintrnational.org and on Facebook, by searching

community forests international.

One of 14 low-cost nursery that Brinkma & Associates, and their planters have helped

establish on the Island. Pemba, Tanzania 2012

Jeff listens as Mbarouk, Executive Director of Community Forests Pemba (CFP) speaks

to community members about the tree planting project.

Community members inspect their recent plantings of mangroves near Wete, Pemba.

Mangroves are planted to help prevent erosion in inter-tidal zones and create rich

habitat for many fish species. 2010

12 Silviculture

A glance back in time:

Poor decision making

Words & Photos by Raymond M. Keogh

Clonal Teak, a revolution in teak cultivation.

13

The year 2012 marks my official retirement date. Normally

retirement is a time to highlight one’s outstanding achievements and

contributions. Unfortunately, as I glance back I see more shipwrecks

than completed voyages. It is difficult to admit this; but my career

was almost a total failure. If I seek excuses, I have few. I must place

the blame on a lot of poor decision-making on my part.

The first poor decision was my choice of career. I could not have

become a forester - and especially a tropical forester - at a more

inopportune time in history. Throughout the period 1972-2012

deforestation in the tropics was running at historically high rates,

reaching on average, 13 million ha/annum in recent years.

The second inadequate decision was to concentrate on teak.

The species has been in decline over the last four decades.

Although 30 million ha were under teak forests in the early 1990s,

resource depletion had gone beyond the point of sustainable

commercialisation by then. Logging bans had to be applied in

Thailand in 1983; India in 1987 and Laos in 1989. Even in

Myanmar, where commercial management has continued to the

present day, the extension of teak forests has been reducing;

the quality declining and the yield dropping. This reflects poor

management. Little wonder, then, that the country is set to ban

exports of the species by 2014.

The third ill advised decision I made was to become involved in

development, yet maintain an emphasis on commercial aspects of

forestry. The focus in the early 1970s was changing from industrial

activities towards community, social or agro-forestry; that is: forestry

for the people. As commercial activities and wood production began

to be marginalised and, as donor funding shifted in line with these

trends, teak as a species for development was sidelined. Counter to

the norm, I continued to develop models for growth and yield in teak.

Lopsided development

In the wake of the change of emphasis from commercial to social

endeavours in forestry, a major problem has become apparent.

Demand for commercial high-grade tropical hardwoods, running at

around 90 million m³per year, depends largely on deforestation and

degradation of natural forests. The unsustainable nature of the supply

situation is known as the tropical hardwood crisis. I do not suggest

that social dimensions should have been ignored; the mistake was to

have created an imbalance. If any aspect of forestry is ignored, the

consequences will be detrimental to the sector as a whole.

During the 1980s, development agencies did make a concerted

attempt to combat tropical deforestation which became a highly

publicised global concern. The Tropical Forestry Action Programme

(TFAP) was an effort to get to grips with a problem that had reached

alarming levels. However, some NGOs, claiming to represent the

environmental movement, accused TFAP of irresponsibility because

it considered logging natural forests. TFAP protested that its aim

Inspection of teak, Brazil.

14 Silviculture

was to shift dependency

of tropical timber supply

from unsustainable to

sustainable practices. As

a result of the disaccord,

donor governments were

confused about which

policy to follow; they

did not support TFAP

adequately and the

initiative sank.

It has become clear that

an inordinately large

area of the natural

forests, running to tens

of millions of hectares

would be required to

sat i s f y sus tainable

commercial demand

for tropical hardwoods.

Most of this area is totally

inaccessible. Therefore,

dependency on natural

ecosystems alone for the

supply of these timbers is

not feasible.

The lack of complementary commercial high-grade hardwood

plantations to take the pressure off natural forests must be addressed.

But, some influential entities question any organisation that considers

developing industrial plantations, especially monocultures, to solve

the crisis. Monocultures are deemed to be a bad thing among

these groups. As a result the donor community has been reluctant

to appear to be supporting commercial plantations.

Without a concerted effort to manage natural forests in a sustainable

manner on the scale required, and without creating backup

commercial plantations, where is the supply to come from? The only

logical answer is that - in the absence of a comprehensive workable

programme - supply will continue to come from deforestation and

degradation until it runs out. Then the world will have to accept that

tropical hardwoods are a thing of the past.

It can be seen that tropical forestry, under the influence of

development agencies and NGOs over the last four decades, has

tended to focus on a select range of priorities. Unfortunately, these

priorities did not embrace the comprehensive needs of forestry. The

creation of tropical hardwood supply sources on the scale required to

satisfy the growing market demand was neglected. Towards the end

of the 1980s the real significance of lopsided policies became clear.

Unscrupulous elements could see clearly that predicted shortages of

tropical hardwoods pointed to very promising returns. They discovered

that teak is a unique hardwood and, unlike many other species in its

category, can be grown in plantations. Its silviculture is well understood

and it is a relatively rapid volume producer given the right conditions.

They presented logical and seemingly watertight cases to attract

investments on a large scale to new plantation schemes. Unfortunately,

their main objective was to make money quickly.

A number of new companies

generated exaggerated forecasts

of growth for the species and

combined these predictions with

prices that were only applicable

to the best-quality forest teak. The

combination of inflated growth

rates and prices produce exciting

predictions about returns for

investors who had little technical

or financial knowledge about the

species. It was regrettable that

the development agencies and

NGOs, which had neglected

the hardwood sector had, by the

late 1980s, lost their authority to

provide a professional opinion

to counter the deceit and in the

vacuum a rash of questionable

retail schemes mushroomed

around the world.

Failure to regain balance

I set up TEAK 2000 (currently

TEAK 21) in 1996 to combat

the hardwood crisis and redress

the imbalance. The organisation

recognised the many barriers to success, including the need to:

• Obtain a sustained output of hardwoods from managed forests

combined with new plantations on a large scale;

• Attract the high levels of long-term finance required through

innovative methods (e.g. through insurance and pension funds;

forest bonds and many other instruments);

• Incorporate a wide spectrum of growers into the endeavour,

particularly communities working with the private sector;

• Overcome technical barriers, including the lack of:

- Superior genetic material for plantations;

- Flexibility in silviculture to suit different categories of growers;

- Wide application of best-practice management techniques;

- Optimal use of good quality land for hardwoods - without

depressing food supply;

- Production of certified high-quality end products;

• Change attitudes, particularly amongst donors, governments

and NGOs in an era of environmental and social forestry in

which timber production on an industrial scale was regarded

with some suspicion.

The Consortium Support System (CSS) was the proposed mechanism

through which TEAK 21 would develop a sustained supply-base of

hardwoods for the marketplace in the long term. The components of

the CSS include services (overall coordination, investment facilities,

technology transfer, tree improvement and quality control) and

Inspection of teak, Brazil.

Indonesia Old Teak; a sight

that is increasingly rare as

time passes and quality teak

disappears – high quality teak

of old age

15

support entities (governments, international

donor agencies and NGOs).

Unfortunately, TEAK 21 failed to make

headway and is to be closed down. I

cannot exonerate myself from this failure

and readily admit - in hindsight - that I did

myself no favours by persisting to persuade

development organisations, despite their

clear reluctance to engage. This was the

fourth ill advised decision of my career.

I feel strongly that the aid agencies and

many NGOs have been prevented from

embracing the CSS because of a groupthink

mentality that is uncomfortable with

timber production on a large scale, and

particularly with the involvement of the

private sector despite their potential in the

development field. Whatever the reasons

for past failures, the tropical hardwood

crisis has not abated and the TEAK 21

proposals are every bit as valid today and

more urgent than they were in 1996.

Looking back

I now look back and contemplate my

career. After writing and speaking many

hundreds of thousands of words in defence

of tropical forestry and teak, I ponder on

this expenditure of time and effort; my

words have not changed the situation for

the better. I also ponder on what I should

have done with my life. The wisdom of

Jonathan Swift springs to mind. I use

his wisdom to illustrate an answer to

my question, though I take the liberty to

change some words (in italics) to suit the

point.

“That few campaigners, with all their

schemes, are half so useful ... as an honest

forester; who, by skilful draining, fencing,

manuring, and planting, hath increased

the intrinsic value of a piece of land; and

thereby done a perpetual service to his

country.”

The future of teak in Latin America (mechanical

harvesting in Brazil).

16 Silviculture

By John Betts, WSCA Executive Director

Western Canada

WSCA 2013 annual conference to

fathom forest restoration

Forest restoration is a term likely to get

more use here in B.C. as we head into

the uncertainties of life after the mountain

pine beetle plague. It makes sense, given

that whatever tactical opportunities we

had to mitigate the extent of the attack are

mostly over. We are now in what we might

call a post-mountain pine beetle phase of

forestry. It would seem provident then to

think about putting things back in order.

Of course it’s not that simple. The term

itself is problematic. To restore means to

return to some previous state. Not only is

that a doubtful possibility, there is good

reason to not want to put things back where

they were on the landscape previous to the

plague. After all, some of those conditions

contributed to the present catastrophe.

Nevertheless, if we are going to use the

word ‘restore’ the question becomes,

‘Restore to what’?

We need to look at the assumption that

is driving the idea of restoring our forests;

the beetles may have eaten themselves out

of house and home. But does the collapse

loose on the landscape; our success in

managing that was minimal. Nevertheless,

any forest restoration strategy needs to

imagine a future landscape that is at least

more resistant to the kinds of catastrophic

disturbance we have just been through.

And, although it is far from ideal, any forest

restoration strategy will likely have to use

the resources we have available today,

which are minimal.

How we attempt to manage our provincial

forests has always been dependent on

public policy. At this point it is critical to see

what vantage point our political and public

planners occupy on forest restoration by

asking them what they think restoring our

forests means in policy and practice. We

intend to do that at the WSCA conference

in February 2013 in a panel which

includes leading politicians on forestry

and members of the senior echelons of

the ministry responsible for forestry. From

that discussion we should be able to infer

the scale and depth of the thinking today

on what might be meant by the concept of

restoring forests for the future.

of their population signal the all clear

when it comes to future disturbances and

consequences of the plague? We already

know the answer to that. It doesn’t. The

plague has created opportunities for fire,

floods, and other bugs and blight that

we are just beginning to contend with.

Ecologically speaking, things are far from

over. And this is to say nothing about the

social and economic effects.

There is another dimension to this as well.

What if the beetle plague is actually a

deeper, less obvious problem announcing

itself? The remarkable damage we’ve seen

may really be an effect, not a cause. If that

is the case then, that cause may not be

gone and will seek other ways to express

itself on the landscape. If we are planning

on restoring our forests, it will do us little

good in the long run to be fixing the wrong

problem.

Which brings us back to just what state

we want to restore our forests to. There

is a whiff of hubris here, of course, in the

assumption that this is something we could

actually do. The beetle plague is a stunning

example of the kinds of forces that can let

17

By Allison Hands

Ontario Forestry Association Will Explore

‘Our Working Forest’ for 64th Annual Conference

The Ontario Forestry Association (OFA) will be hosting its 64th

Annual Conference on February 8th in Alliston, Ontario. ‘Our

Working Forest’, the 2013 theme, will focus on the importance of the

forest industry, the contributions that forestry makes to our economy

and culture, and the opportunities that forests present to Ontarians.

The OFA hopes to restore the image of the industry using our

annual conference as an opportunity to engage landowners, forestry

professionals, students and the general public. Our Working Forest

will bring together experts from industry, academia, government, and

more to discuss the state of forest products today, what to expect in

the future, and what this means to all of us.

“Ontario’s forests can work for all of us, providing important

economic, ecological, and recreational opportunities,” said

Margaret Casey, OFA director and conference chair. “The message

we are trying to get through is that whether you are a practitioner,

woodlot owner, or any other interested individual, there are benefits

to managing your forests, both on a landowner and provincial scale.

While there may be differences between these two scales, there are

many similarities as well.”

Casey admits that the theme is slightly different than previous

years. “There is a greater focus on the forest industry and finding

what a working forest means to landowners in Ontario. Previous

conferences have been more about science and research, including

talks on the emerald ash borer two years ago.” This year, OFA is

planning a pre-conference session for municipal forest managers

on EAB in partnership with York Region on February 7th as a way

of addressing this critical issue. This will allow the OFA to focus the

conference on providing new information to the public and creating

a greater connection and awareness of the forest industry in Ontario.

The conference will open with a plenary session that will address

‘What is the Working Forest?’, and highlight the successes of a

working forest in Ontario. Peter Schleifenbaum, owner of Haliburton

Forest and Wild Life Reserve, will speak of his property and how

he utilizes his forest land. “It will bring a unique perspective to the

audience and get everyone on a good thinking path first thing.”

Two streams will run concurrently throughout the day, one focusing

on Ontario’s Forests and the other a Landowner’s Toolbox. The

Ontario’s Forests stream will cover topics such as forest ecology,

Algonquin Park as a working forest, and even the successes of

local wood products, with the goal of highlighting the value and

importance of our provincial working forests.

The Landowner’s Toolbox stream will focus on helping woodlot

owners get the most out of their forests and include talks from

those working directly in the forest such as loggers and forest

consultants, giving the audience a more in-depth view of how they

work. “The sessions will provide woodlot owners with information

and encouragement on using professionals and the critical questions

they should be asking them,” Casey said.

“I really see this event as getting people to think in a positive

way about the forest and its role, but also being practical for the

landowners and getting them to look at the future,” Casey said of

the conference.

Previous years have enjoyed near capacity numbers with over

300 people, and Casey expects the same turn out again this year.

Registration is limited so those interested are encouraged to register

early.

The conference theme will be a leading force for the OFA in the

coming year, with the goal of increasing the public’s awareness of

forestry in Ontario including forest ecology, careers and sustainable

management of our resources. Successful programs such as Focus

on Forests and Forester in the Classroom aim to reach teachers

and students in engaging curriculum linked resources. For more

information about the OFA, visit www.oforest.ca

Ontario Report

18 Silviculture

An introduction

The International Forestry Students Association (IFSA) is an incredibly

diverse organization that unites students of forestry/forestry-related

sciences from every corner of the globe. IFSA’s vision is for global

cooperation among students of forest sciences in order to broaden

knowledge and understanding to achieve a sustainable future for

our forests, and to provide a voice for youth in international forest

policy processes.

IFSA’s mission is to provide a platform for students of forest sciences

to enrich their formal education, promote cultural understanding by

encouraging collaboration with international partner organisations

and to gain practical experiences with a wider and more global

perspective. Through its network, IFSA encourages student meetings,

enables participation in scientific debates, and supports the

involvement of youth in decision making processes and international

forest and environmental policy.

By Katie Gibson

International Forestry Students’ Association

IFSA also maintains excellent partnerships with international forest

related organizations which include the International Union of

Forestry Research Organizations (IUFRO), the European Forestry

Institute (EFI), the Commonwealth Forestry Association (CFA), the

Food and Agricultural Organization (FAO), the Informal Forum

of International Student Organizations (IFISO), the Centre for

International Forestry Research (CIFOR), and the International

Tropical Timber Organization (ITTO). It works with these

organizations to offer students opportunities to get involved in the

professional world of forestry. These organisations are also provided

with access to the largest collective potential workforce/ thinking

body of forestry students.

IFSA is open to forestry students from all academic levels and offers

a wide array of opportunities and activities. It coordinates social,

professional and educational meetings amongst its members,

arranges internship prospects, provides professional training, and

allows students to get involved in international processes.

It is strictly a student-run association; all activities and meetings are

solely organized and managed by students. In this sense students

who take on official positions within the IFSA gain a stupendous

amount of experience in being involved with such a professional,

multinational organization.

IFSA organizes an annual symposium for its members which takes

place in a different country each year. Students come from all over

the world to take part in the memorable two week event in which

they get a forestry-focused tour around the country. The most recent

symposium occurred in Turkey; it will be in British Columbia, Canada

in the begininning of August, 2014.

Katie Gibson is Vice President of the IFSA and can be reached at [email protected].

19

First Nations Forestry Council supports communities and

silviculture through business and training

The First Nations Forestry Council (FNFC) understands the

importance of silviculture and is excited to be involved in supporting

communities through the creation of, or participation in, programs

that support the best management of our lands and resources.

FNFC is in its seventh year of operation as a non-profit society

supporting all First Nations in their forestry activities. We promote

First Nations business opportunities in forestry, and collaborate

with government on forestry programs and issues such as tenure,

Forests for Tomorrow program and policy development. The FNFC is

known to design programs and policies that align with First Nations

and government goals, provide forestry information to First Nations

communities, and works to address First Nations forestry priorities.

Current priorities include business development in forestry,

health and safety around the MPB infestation and resulting fuel

management and, always important to First Nations-health of the

lands and resources. Our programs have included understanding

the role First Nations are playing in the sector, supporting continued

fuel management reduction around communities and interest in

being part of the forest sector at both the operations economic

development level and at the more senior policy and governance

level.

FNFC is currently implementing a training program designed to

produce skilled workers and independent contractors that can

By Keith Atkinson, RPF

B.C. First Nations Forestry Council

participate in the forest sector. The First Nations Forestry Training

Partnership pilot is a Training Partnership program that we have

launched this year, with the support of the Province of BC. The

program is designed to train aboriginal people for jobs in the forestry

sector, assisting with linking employers with these students and

bridging the tremendous labour gap that the forest sector predicts

for the coming decade.

Students entering the program will be applying for forest sector

related training and they will align themselves with a forest industry

sponsor. There are multiple streams for training as the goal is as

much recruitment of forest sector workers as it is in the training.

Industry sponsors are supporting the individual with their academic

goals and are providing a work term placement.

This type of partnership program is designed to recruit students, to

provide solutions for the forest sector labour shortage, to bridge gaps

in education and skilled labour, and to build relationships between

forest sector business and First Nations communities.

The FNFC is committed to assisting First Nations communities and

youth interested in forestry in moving forward and contributing to the

best management of our forests – we feel there is a current need for

increased silviculture and restoration activities on the land and we

hope to assist with the relationships and partnerships that are needed

to encourage a collaborative approach to addressing this need.

Sign up on our home page to receive each quarterly issue by email.

Check us out on Twitter @SilvicultureMag, and on Facebook.

Do you get Silviculture Magazine

delivered directly to your inbox?

Silvicu M A G A Z I N E ture

20 Silviculture

By Vicki Gauthier

Saskatchewan Report

Jack Pine and June Bugs – A Deadly

Combination in Saskatchewan!

Jack pine (Pinus banksiana) is an important

tree species to Saskatchewan. Of

Saskatchewan’s commercial tree species,

jack pine makes up approximately 17 per

cent of the provincial forest types (PFT) in

the commercial forest and over 38 per cent

of the PFTs in an area called the Island

Forests. The Island Forests in Saskatchewan

are located within a transition area between

boreal forest to the north and grasslands to

the south (the Boreal Plains ecozone). This

region marks both the southern advance

of the boreal forest and the northern limit

of arable agriculture (Acton, Padbury

and Stushoff 1998). The area of interest

is described as a sandy loam site that is

prone to drought and was heavily infected

with Lodgepole pine dwarf mistletoe

(Arceuthobuium americanium) and was

also disturbed by wildfire in 1995. The

Lodgepole pine dwarf mistletoe has the

most significant impact on the Island Forests

with more than 13 per cent (26,453 ha) of

jack pine infected with this parasite.

However, another pest of interest to the

Island Forests was discovered in the fall

of 2011: the June bug! Appropriately, this

story of jack pine and June bugs begins in

June of 2011. An area of land that was

not sufficiently restocked (NSR) in the Island

Forests was fill-planted using jack pine

412 (1+0) container stock planted at 2 m

spacing. By the fall of 2011, dead seedlings

had been discovered in this plantation

during a routine walk through. When the

seedlings were dug up to determine cause

of death, it was very strange to see that

the entire plug (4 cm across and 12 cm

long), the radicle and all lateral roots were

stripped from the seedlings (see Figure 1).

As we do with all things related to dead and

dying trees here in Saskatchewan, the dead

seedlings were brought to our provincial

forest entomologist and pathologist, Dr.

Rory McIntosh. He diagnosed the damage

to be consistent with the work of June

beetles: the pesky Phyllophaga spp. (Figure

2)! Dr. McIntosh provided the following life

cycle description.

The common life cycle of the destructive

and abundant Phyllophaga spp. extends

over three years. While these white grubs

Acton, D.F., G.A. Padbury, C.T. Stushoff. March, 1998.

The Ecoregions of Saskatchewan. Prepared and edited by

Saskatchewan Environment and Resource Management.

Canadian Plains Research Centre/Saskatchewan Environment

and Resource Management. University of Regina. 205 pgs.

Vicki Gauthier is a professional forester with the Saskatchewan

Ministry of Environment.

normally feed on grass roots, they will eat

the roots of tree seedlings, especially when

grass roots are scarce, as was the case in

the Island Forests. In May or June the adult

beetles will emerge from the soil and feed

on broad-leaved hardwoods. The adults

mate in the evening (how romantic) and at

dawn the females return to the ground to

deposit 15 to 20 eggs, one to eight inches

deep in the soil. Eggs hatch about three

weeks later into the young larvae that feed

upon the roots and decaying vegetation

throughout the summer. In the fall, they

migrate downward in the soil, to a depth

of up to one and a half metres, and remain

inactive until the following spring. The

spring can see the most damage as the

larvae return near the soil surface to feed on

plant roots. Seedling plugs that are J-rooted

because of careless planting are often killed

first. In the autumn, the larvae again migrate

deep into the soil to overwinter, returning

to just below the soil surface for the third

spring to feed on plant roots until they

are fully grown by late spring. The grubs

then form oval earthen cells and pupation

begins! The adult emerges from the earthen

cell a few weeks later, but doesn’t leave the

ground just yet. The beetles overwinter and

emerge the following year in May or June,

when the next round of feeding, mating and

egg-laying takes place.

You can see how by the fall of 2011 the

larvae had already eaten the roots from

the jack pine plugs in the Island Forests and

left evidence in the red, dead seedlings.

It is estimated that up to 250 hectares

of plantation have been damaged, or

approximately 270,000 seedlings. The cost

of re-treating these sites could be as much

as $300,000. The June bug is native to

Saskatchewan and generally has a threeyear

cycle. We estimate that 2011 was year

two of the cycle. The grubs we found this

past spring indicate that 2012 is year three

and, hopefully, the end of the cycle. We’ve

got our fingers crossed that replanting these

sites in the spring of 2013 will avoid major

root damage and allow the seedlings to get

bigger and be better able to withstand any

further June beetle attack.

Figure 3: Dead Jack pine with damaged radicle.

Photo by Rory McIntosh. Ministry of Environment

Figure 1: Dead jack pine with june bug.

Photo by Christine Simpson. Ministry of Environment

Figure 2: June bug.

Photo by Christine Simpson. Ministry of Environment

21

The ultimate tree

planting shovel

By Ting von Bezold

Every planter spends countless hours

daydreaming ways to improve the activity

of planting trees. During one such session I

contemplated how to improve my planting

shovel and recalled meeting a knife maker

on Salt Spring Island, Seth Burton. I was

imagining modifying my existing stock shovel

with a handle made of Damascus steel. One

of the many downfalls of today’s modern

planting shovel is that the handles are prone

to failure. Damascus is an ancient form of

steel characterized by distinctive patterns

of banding and mottling, reminiscent of

flowing water. Items made of Damascus are

reputed to be not only tough and resistant

to shattering, but capable of being honed

to a sharp and resilient edge, ideal for knife

making. It was just a few years prior that I

had met Seth and was introduced to his

exquisite hand forged knives made from

Damascus. I bought one as a gift for my

tree planting boss.

I soon visited Seth on Salt spring Island

and sowed the idea of modifying my shovel

into the ultimate planting machine. To my

delight, Seth was interested. A shovel is, after

all, a type of blade and the idea of making a

blade that cut through tough terrain to plant

trees motivated him. We decided to work on

this project together.

Like a true piece of art the design didn’t

occur overnight. Over several months the

design emerged with a blade of Damascus

steel rather than the handle. As we worked,

there was an unspoken understanding

between us that we were going for the

absolute best shovel possible. In the end the

only thing we used from the original shovel

was the general size and weight. The final

construction is what we consider to be the

best tree planting shovel made to date. In

fact it is probably the most beautiful and

functional shovel ever made.

The blade and ferrule was constructed

out of five types of the highest quality

stainless steels, forged and folded over

a core of powdered tool steel. The result

of this process was a single billet of metal

consisting of over 200 layers. Having not

made a shovel blade before, Seth drew on

his considerable metal smith experience

to find the combination of inert hardening

and tempering that would produce a shovel

blade that was both tough enough to

endure repetitive striking against rock and

which had high edge retention (capacity to

remain sharp). After mastering the blade

we moved onto designing the handle,

shaft and fittings. For the shaft, we chose

a wood, Cocobolo, known for its strength

and weather resistance. Cocobolo has been

used for centuries in knife and gun handle

construction. The shaft was press fit, epoxied

and pinned with a mosaic pin into the

ferrule. The D-handle was constructed with a

white oak core and reinforced with stainless

steel. A mortis and tenon and stainless steel

bolt fastened it to the shaft. The final touch

was to wrap the D handle in multiple layers

of carbon fibre. The last stage of the shovel

construction was the grip which we formed

out of stacked leather with a half inch square

stainless tang and bolster.

Two hundred and fifty thousand trees later,

the shovel still looks brand new and is valued

at over $6000. Most standard shovels would

struggle to last a single season of planting

and certainly would not be considered a

valuable piece of art. This shovel will last

forever. Eager to try the shovel, a fellow

planter Wahabu Ahmed, renowned for his

19 year tree planting career, borrowed the

shovel for a month and attests:

“I got the opportunity to try this shovel at the

later part of this planting season and I can

say it is the best shovel I have used in my

nineteen years of planting. The shovel feels

solid and the blade has the best approach

angle, which makes it easier to drive through

challenging land such as thick grass.”

Feats and achievements aside, I humbly

suggest the best thing this shovel has done

is cultivate a friendship that is destined to

grow along with all the trees this shovel has

planted. Thank you, Seth Cosmo Burton.

22 Silviculture

Forest Health

be identified for reserve selection and

cone collection. Stocking standards can

incorporate whitebark pine as a preferred

or acceptable species if accompanied

by a professional rationale in support

of objectives for wildlife or biodiversity.

Whitebark pine stands, especially those

with many cone-bearing trees and in good

health, are good candidates for wildlife

tree reserves, Old Growth Management

Areas, and Wildlife Habitat Areas for

grizzly bears.

In areas planned for harvest, it is now

important to prioritize conserving and

identifying trees which appear to lack

blister rust cankers. These trees may be

rare disease-resistant genotypes, thus

providing a life-link to the species’ future in

the area since resistance to blister rust can

be passed down from the parent trees to

their seedlings. Currently, every state and

province that administers whitebark pine

is identifying, testing, and propagating

disease-resistant progeny capable of

surviving blister rust. Thinning can benefit

whitebark pine by targeting and removing

competing tree species. Opening up

canopies often improves reproduction of

whitebark pine by attracting seed-caching

Clark’s nutcrackers and providing better

light conditions for pine seedling growth.

These seed caches are the primary way

that whitebark pine regenerates. As an

example, in the East Kootenay Region,

BC Timber Sales (BCTS) has adapted the

following guidelines.

• Stands with less than 50% mature

composition of whitebark pine. Cankerfree

trees should be clearly identified and

retained throughout the harvest area,

especially trees that have robust crowns

capable of producing many cones.

Proceed with care to avoid damaging these

trees.

By Michael P. Murray and Jodie Krakowski

Whitebark pine (Pinus albicaulis), wellknown

for its value to western North

American high-mountain wildlife,

commonly thrives in harvested forests. As

the producer of the largest tree seeds in the

spruce-fir zone, whitebark pine supports

more than two dozen species of foraging

mammals and birds, including grizzly

bear (Ursus arctos horribilis) and Clark’s

nutcracker (Nucifraga columbiana). The

tree maintains waterflows into the dry

summers by shading late-lying snow. At

the highest elevations, their wind and ice

battered frames contribute to spectacular

timberline scenery.

An introduced fungal pathogen (Cronartium

ribicola) known as white pine blister rust is

decimating whitebark pine throughout

most of its range. This canker disease has

a complex lifecycle, but in general, the

younger or smaller a tree is, the quicker it

dies. Larger trees may survive for decades,

however stem cankers will often kill crown

tops. This is where most of the valuable

cone-producing branches are. Whitebark

pine grows so slowly, trees often need

to reach ages of 50 to 80 before they

produce cones.

In southeast British Columbia and

southwest Alberta, most whitebark pine

are dead or dying from blister rust. The

mountain pine beetle (Dendroctonus

ponderosae) epidemic has accelerated

the decline, causing great concern since

the beetle prefers mature trees which

produce the most cones. Many whitebark

pine populations are further stressed by

increasingly crowded stand conditions. This

is a reflection of mandated fire exclusion.

By eliminating natural fires, less fire-hardy

competitors such as Engelmann spruce

(Picea engelmannii) and subalpine fir

(Abies lasiocarpa) have prospered to the

detriment of whitebark pine, which is not

a strong competitor.

Recognizing the mounting pressures on

whitebark pine and dependent wildlife,

the Canadian government classified it as

endangered in June 2012. It is the first tree

in the West to receive this declaration. As

of this writing, restoration planning is in

the earliest stages and there are no rangewide

government restrictions on whitebark

pine harvest or use. However, some forest

licensees have already incorporated

tree retention guidelines in their formal

plans (e.g. Spray Lakes Sawmill, AB and

Canfor’s operations near Cranbrook,

BC). While the government of Alberta is

nearing completion of its own recovery

plan for crown lands, individual forest

plans (e.g. C5 and R11) have articulated

whitebark pine retention guidelines. The

BC Forest Service has issued an informal

bulletin providing general information and

recommendations for avoiding harvest

(www.whitebarkpine.ca/publications.html).

W h i t e b a r k p i n e o f t e n a c h i e v e s

merchantable form in forests of mixed

species. From 2000-2009, harvested

volume in BC’s Southern Interior Region

was at least 21,388 cubic metres (based on

scaling records). Forest practitioners can

creatively maintain and promote whitebark

pine within managed stands, thus averting

complete loss throughout its range. Studies

indicate that with active management, it’s

possible to significantly improve whitebark

pine habitat.

Forest professionals can provide clear,

measurable and verifiable direction and

silvicultural support for whitebark pine

through Forest Stewardship Plans (FSPs)

and landscape level planning. Species

at risk, including whitebark pine, may be

addressed through stand-level biodiversity

measures and wildlife as FRPA (Forest

and Range Practices Act) values in an

FSP, where high-value individuals may

Silvicultural Options for the Endangered Whitebark Pine

23

• Stands with more than 50% mature composition of whitebark

pine. Exclude stands from harvest through group tree retention such

as removing these timber types from the harvest area, designating